High-Risk Countries in the German National Risk Assessment – What Does It Really Mean?

This post analyses Germany’s National Risk Assessment country list.

Bernhard Obenhuber

Jan 22, 2026

On 1 December 2025, Germany’s financial supervisor BaFin published a new circular (“Rundschreiben 13/2025”, Link) addressed to all supervised entities. The document focuses on third countries with deficiencies in combating money laundering (ML) and terrorist financing (TF) and reiterates the obligation to monitor various international country lists.

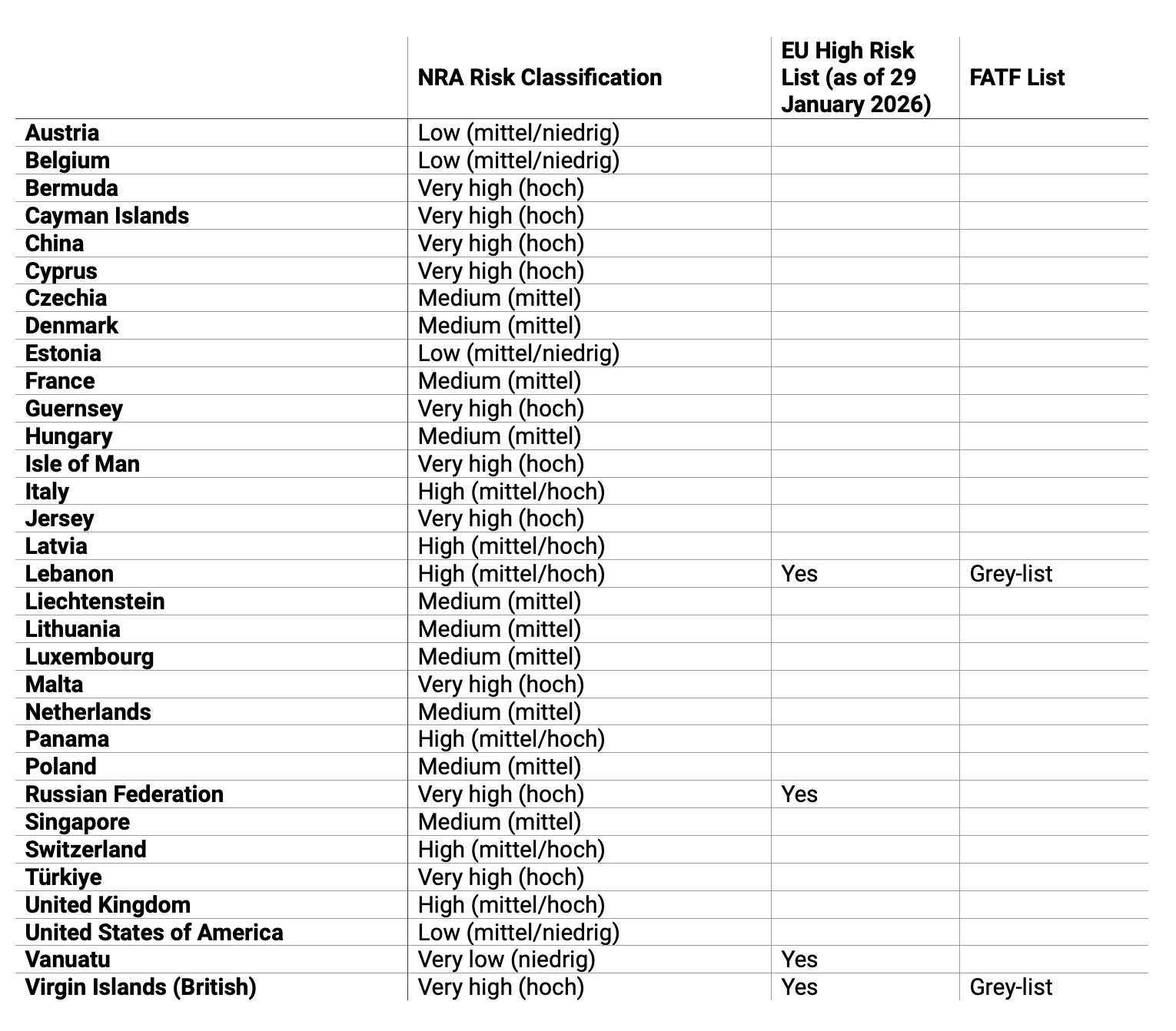

BaFin explicitly refers to the FATF black list (currently covering North Korea, Iran and Myanmar), the FATF grey list, and the EU list of high-risk third countries. These lists are familiar territory for compliance teams. FATF black-listed and EU high-risk countries trigger enhanced due diligence requirements, while FATF grey-listed countries require closer monitoring without automatically triggering additional measures. The update cycles differ: FATF revises its lists three times a year, while the EU updates are less frequent, with the next one entering into force at the end of January 2026.

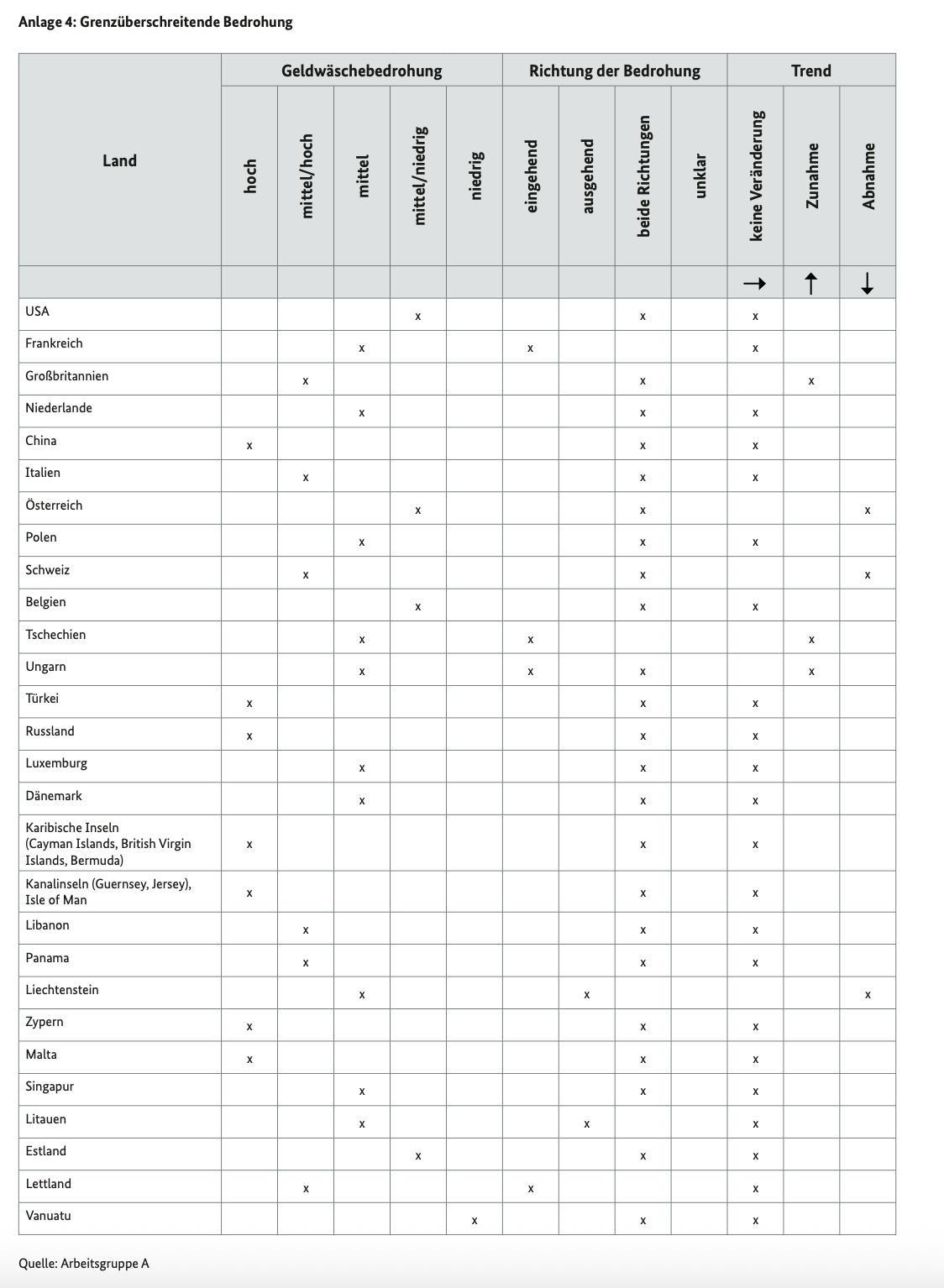

So far, the regulatory expectations are clear and well established. However, the final sentence of the BaFin circular introduces a layer of ambiguity. It states that, in addition, the findings in Annex 4 of Germany’s National Risk Assessment (NRA) on cross-border threats must be “taken into account appropriately.” This wording immediately raises questions. What exactly is Annex 4, and what does “appropriate consideration” mean in practice?

Where Things Get Fuzzy: Annex 4 of the German NRA

Annex 4 stems from Germany’s first National Risk Assessment published in 2019 (Link). It contains a list of countries classified according to their relevance for cross-border money laundering threats. Conceptually, it resembles the FATF and EU lists, which makes its existence somewhat puzzling. Why introduce a national list when European and global standards already exist? And how relevant is a classification that dates back several years?

While the first question remains unanswered, it is clear that Germany is not alone in maintaining a national list. Other European countries, such as France and Lithuania, follow similar approaches. Nevertheless, this fragmentation raises concerns about regulatory consistency and unnecessary bureaucracy across the EU.

The NRA explains that countries were selected based on several criteria, including geographical proximity, the presence of large diaspora communities, economic significance for Germany, and frequent international references to money laundering or terrorist financing risks. What is missing, however, is a systematic country-by-country justification. Instead, the report provides qualitative explanations for selected countries and country groups.

How Germany Defines High-Risk Countries

For Russia, the NRA highlights organised crime networks that launder funds through financial centres such as Frankfurt and correspondent banks in London, Switzerland, Malta and Cyprus, before reinvesting the proceeds in Germany. In the case of Turkey, the focus is on the large Turkish diaspora in Germany and associated remittance flows, as well as Istanbul’s role as a hub for drug trafficking, illegal migration and Hawala banking networks.

China is described as a destination for cash smuggling from Germany, with authorities repeatedly identifying large sums transported on flights. The report also refers to counterfeit goods distributed across Europe by organised crime groups, with profits laundered through luxury purchases and real estate in Germany before being transferred back to China.

Malta and Cyprus are characterised by features of their financial systems that may enable opacity and concealment. The report also points to online gambling activities, including casinos that are illegal in Germany, and to investor citizenship schemes that may facilitate money laundering.

Several offshore financial centres, including the British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Bermuda, Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of Man, are highlighted for enabling the concealment of illicit funds through shell companies and opaque structures.

Germany is also assessed as facing medium-high risks linked to countries such as Lebanon, Panama, Latvia, Switzerland, Italy and the United Kingdom. In Lebanon’s case, the report refers to clan-based organised crime active in German cities, with funds transferred abroad for laundering. Italy is linked to strong economic and personal ties, with evidence of mafia-related money laundering activities in German real estate markets.

What the Cases Have in Common

Across all these cases, a common pattern emerges. Organised crime networks exploit cross-border financial systems, diaspora connections, opaque jurisdictions and real assets to move, disguise and reintegrate illicit funds into the German economy. These are all reasonable risk drivers and largely consistent with international typologies.

However, one statement in the report immediately caught my attention. It claims that Malta “has been running a Golden Visa programme for years.” This is no longer accurate. Malta’s scheme was terminated following an EU court decision, and the country has been removed from the OECD list of problematic investor visa programmes in 2025. While Malta still poses money laundering risks related to online gambling, the reference to an active Golden Visa scheme is outdated and should be corrected.

Does the Data Support the Classifications?

To better understand the rationale behind the German classifications, we compared the NRA list with the FATF (Link) and EU (Link) lists. The overlap is surprisingly small. Only four countries appear on both the German list and the international lists: Lebanon, Russia, Vanuatu and the British Virgin Islands. This raises an important question. Are these differences driven by genuinely different risk assessments, or do they simply reflect Germany-specific relevance criteria, such as migration patterns or trade relationships?

For financial institutions, the practical consequence is clear. They must treat a significantly larger number of countries as high risk, which increases compliance costs and operational complexity.

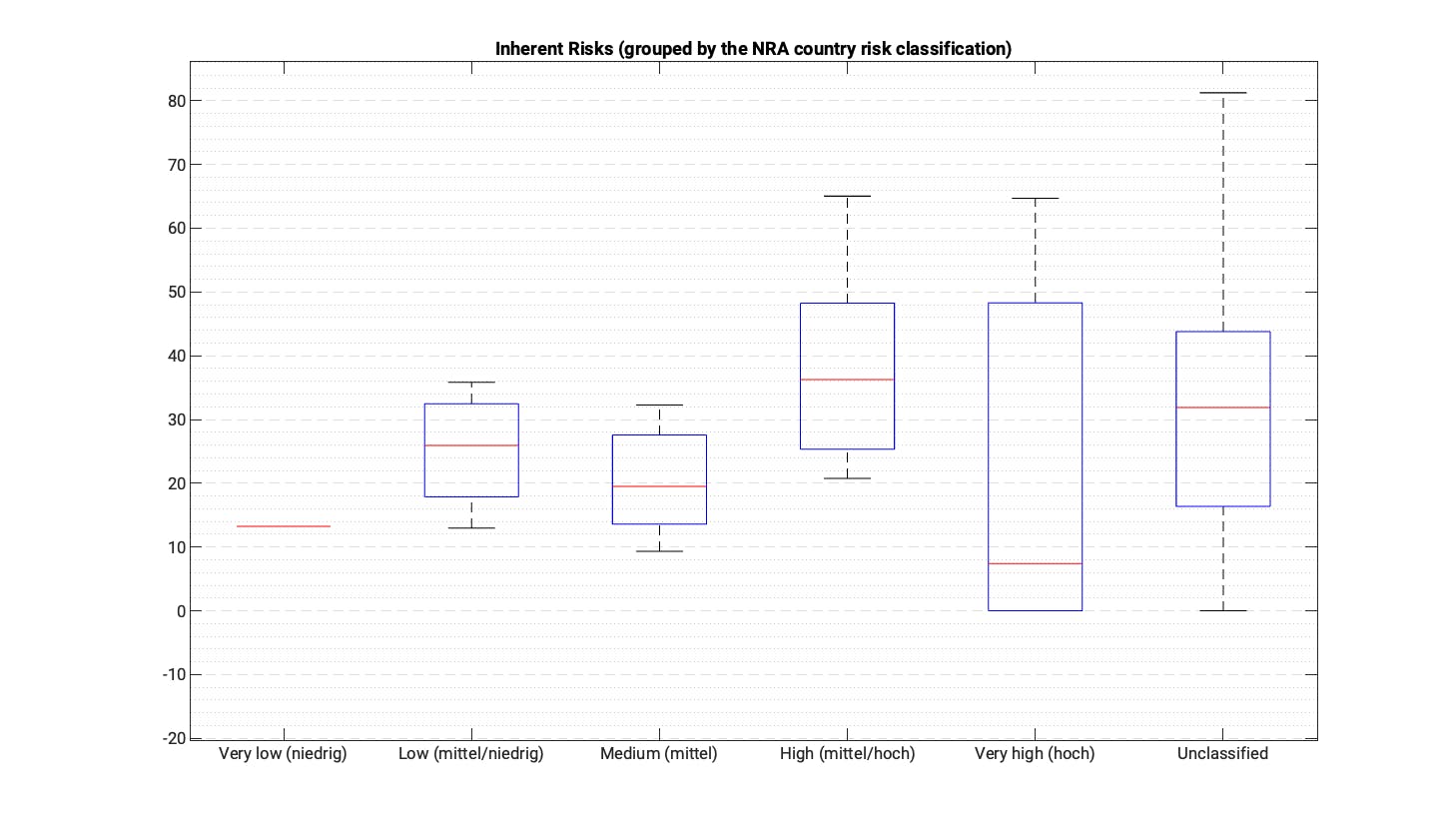

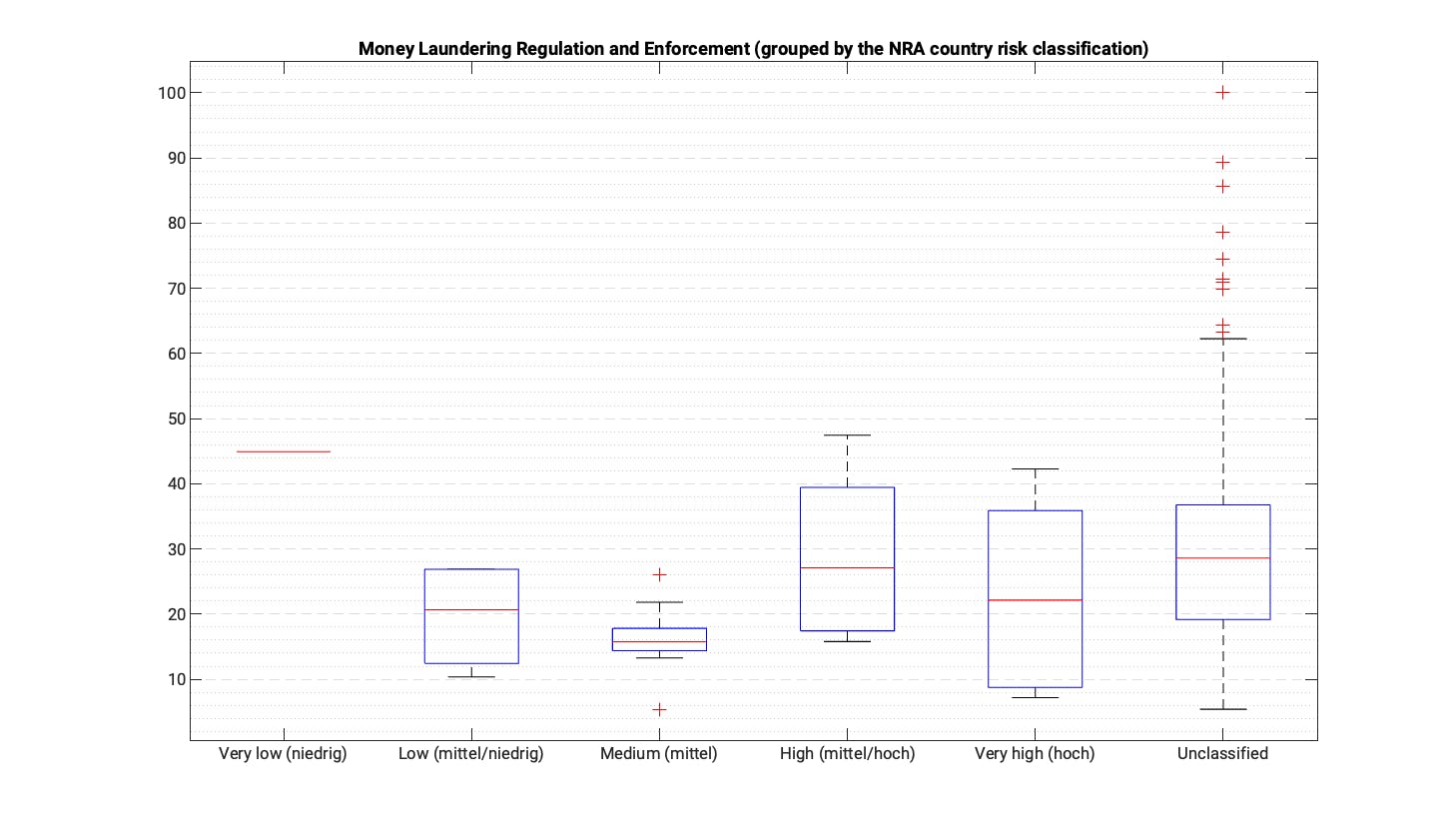

We also tested whether the classifications are supported by quantitative indicators from our AML country risk score. When looking at inherent risk related to predicate offences such as drug trafficking and corruption, high-risk countries generally show higher median risk values. However, the relationship is far from consistent. Countries classified as “very high risk” display a wide dispersion. Russia and Turkey have high inherent risk levels, but jurisdictions such as the Cayman Islands or Jersey are not known for high levels of organised crime. This suggests that inherent criminal risk alone does not fully explain the NRA classifications.

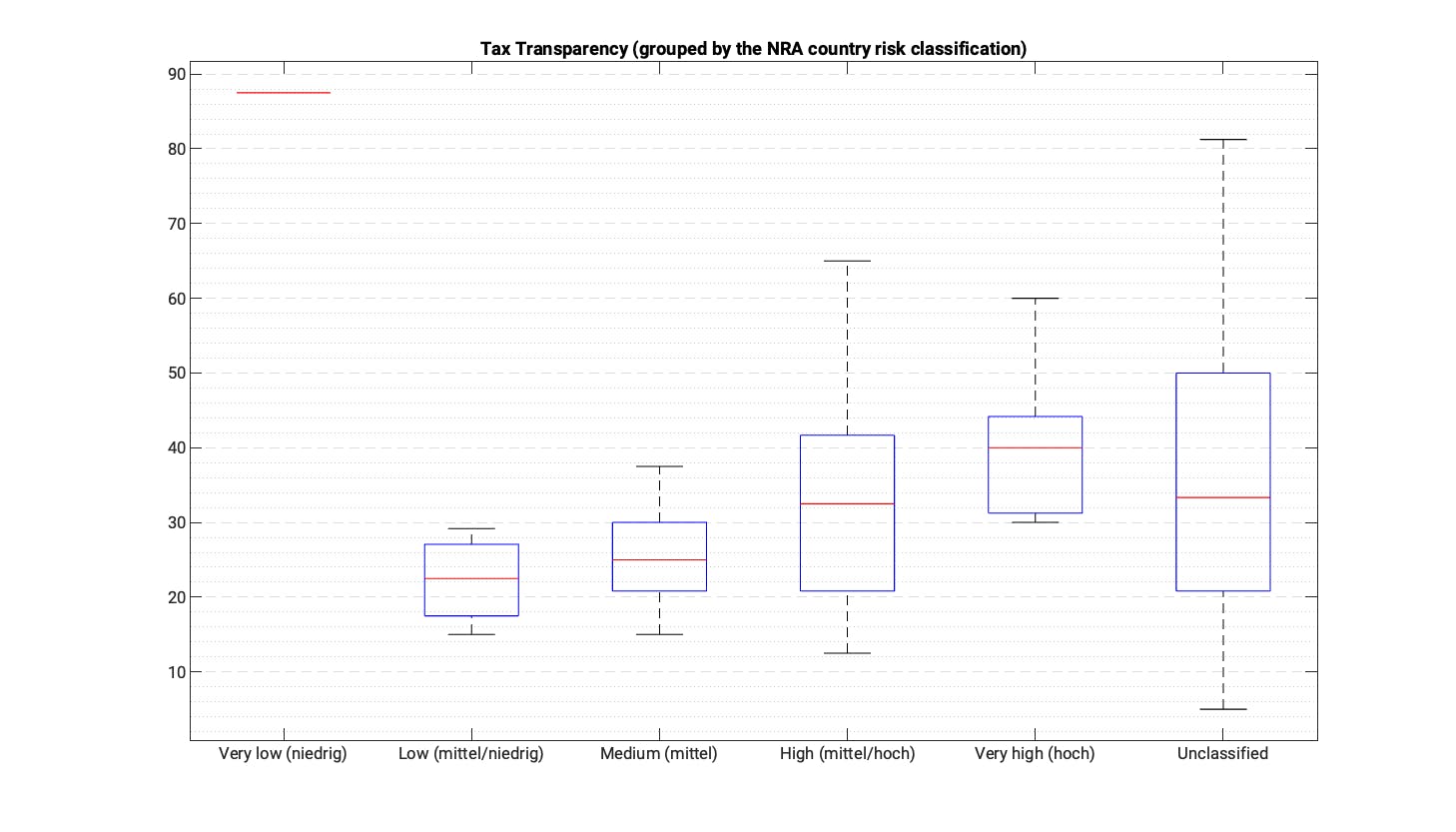

How to read the charts: The box-plots visualise the distribution of risk scores across countries within each NRA risk category. The horizontal line inside each box represents the median value, showing the “typical” country in that group. The lower and upper edges of the box mark the 25th and 75th percentiles, capturing the middle half of observations. The whiskers extend to the lowest and highest values in the group, illustrating the full range of outcomes. A tall box or long whiskers indicate a high degree of dispersion, meaning countries within the same NRA category differ substantially in their underlying risk profiles. Conversely, a compact box suggests a more homogeneous risk pattern. This helps identify whether a given risk classification reflects a consistent country group or masks significant heterogeneity.

A much stronger relationship emerges when looking at financial secrecy and tax transparency indicators. Countries classified as high risk tend to score poorly on transparency measures. This seems to be a key explanatory driver. Interestingly, Vanuatu, the only country rated “very low risk” in the NRA, is a clear outlier, given its weak transparency record and active investor citizenship schemes.

Finally, we examined indicators related to the quality and effectiveness of AML regulation, including FATF ratings and EU classifications. Here, we found virtually no statistically meaningful relationship. Several countries classified as “very high risk” by the German NRA actually have relatively strong AML frameworks and enforcement track records.

Overall, the evidence suggests that financial secrecy and tax opacity are the dominant drivers behind the German classifications, with inherent criminal risk playing a secondary role. Formal AML regulatory quality appears to be far less relevant than one might expect.

Conclusion

Considering country risk lists is a core element of any AML compliance framework. However, we question whether maintaining multiple national lists within Europe, in addition to the EU list, truly adds value. For institutions operating across borders, this regulatory fragmentation increases complexity, costs and legal uncertainty.

While we understand that national regulators have different priorities, greater harmonisation would clearly benefit the market. At a minimum, country lists should be updated on similar schedules and based on transparent methodologies to avoid confusion as the regulatory landscape evolves.

We would be very interested to hear how you deal with the German NRA country list in practice. How do you integrate it into your AML risk assessments, and does it materially change your compliance approach? Get in touch with us at [email protected].